Command and Consent: What the National Guard Ruling Tells Us About Power

Still, the question lingers: who commands the public servants when the public is divided?

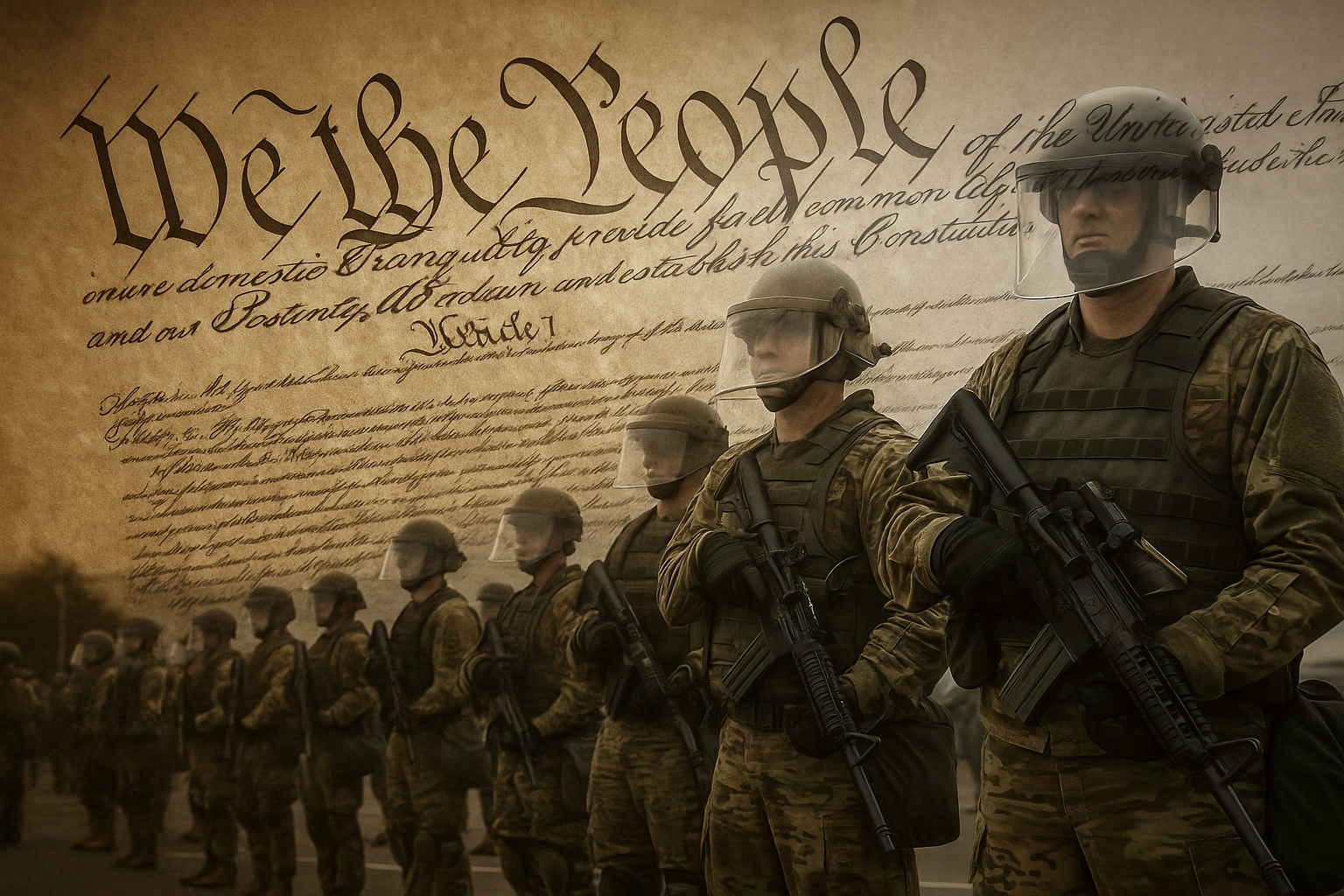

Overnight, a federal appeals court let Donald Trump retain control over California’s National Guard—overriding the state’s elected leadership and setting up a high-stakes legal clash. Here’s a three-judge panel quietly blessing the idea that the president can federalize a state’s Guard even when the governor says no.

It’s not unprecedented. But it’s not normal either.

The last time a president federalized the Guard against a governor’s wishes was in 1965. Lyndon Johnson, confronting George Wallace’s refusal to desegregate Alabama schools, ordered federal troops to protect the rights of Black Americans. That was a confrontation over civil rights, the Constitution, and the brute power of the state. It was ugly, but the logic was clear: federal power was being used to enforce equal protection under law.

This time? The justification was a protest outside an ICE facility in Los Angeles. A few thrown objects. No lasting violence. The court said that was enough to invoke Title 10 authority. Enough to strip the governor of command. Enough, apparently, to tip the balance of federalism in favor of a president who has already shown contempt for democratic norms. It’s all performance. It’s all spectacle. And it’s all happening under the guise of “public safety.”

Let’s walk through what that means.

Under 10 U.S.C. § 12406, the president can call up the National Guard during invasion, rebellion, or when states can’t enforce the law. Trump’s lawyers say the ICE protest met that bar. The appellate court didn’t rule definitively—they just issued a stay—but they found his case likely enough to halt a district court order returning control to Governor Newsom. In doing so, they leaned heavily on Martin v. Mott (1827), a centuries-old precedent that gives presidents broad discretion to decide what counts as an “emergency.”

But discretion isn’t the same as accountability. And this ruling has serious implications for the anti-commandeering doctrine—the principle that the federal government can’t force states to enforce federal law. It also chips away at the Posse Comitatus Act, which bars the use of military forces for domestic law enforcement without congressional approval. This isn’t about routine coordination. It’s about one executive, acting unilaterally, asserting control over forces that—at least in theory—exist to serve both the nation and the state.

And yes, it matters that Trump is the one asserting it.

Because this is the same man who, during his first term, asked advisors about seizing voting machines. Who floated martial law to “redo” the election. Who elevated performance over governance, grievance over law. So when he regains control of California’s National Guard, the question isn’t just whether he can. The question is what that power might be used for.

This isn’t a conspiracy. It’s a structural signal.

If the Supreme Court upholds this precedent—and they might—it opens the door for this and future presidents to claim emergency powers with minimal justification. That might not mean tanks in the streets. But it could mean Guard deployments during elections. Or rapid federalization of state resources in the name of “order.” Or chilling, strategic shows of force when local leaders refuse to comply. The tools are already in the toolbox. What’s shifting is the willingness to use them, and the courts’ growing deference to those choices. To allow the military to be used as a political tool, rather than a neutral arbiter of public safety.

This is where your theory class and your headlines start to blur.

We’re not just watching partisan conflict. We’re living through a fight between two social compacts, like I wrote about here. One compact—call it civic or constitutional—says that institutions exist to mediate conflict, not escalate it. That power flows from the people. That force is a last resort. The other compact—growing louder—is one of domination. It says the state exists to protect “us” from “them.” That consent is optional. That public servants serve the president, not the public.

That second compact thrives in the shadows. In the fine print. In the legal rulings that seem technical but redraw the map of who gets to decide.

So let’s bring this back to public service.

If you’re a city manager, a policy analyst, a National Guardsman, a planner, a teacher, this ruling isn’t abstract. It tells you who might give you your next order. It tells you what kind of power you might be asked to enforce. And it raises a deeper question: are we being equipped to serve democratic institutions, or repurposed to reinforce political control?

There are still checks. Congress can step in. State legislatures can assert their authority. Courts can slow the slide. But none of those work without people inside the system who remember what it was built for. Who refuse to treat government as a stage for grievance. Who still believe that public service means something more than loyalty to the strongest voice in the room.

Keep teaching. Keep writing. Keep talking with your students, friends, kids about what this all means—not just legally, but morally. Because if we don’t hold tight to the older compact, the newer one will keep spreading.

And we’ll wake up one day realizing that the chain of command has changed—and no one asked us first.